(This is a work in progress!)

This page summarizes a 28-day cruise from Miami to Manaus and back to Ft Lauderdale in Feb-Mar 2024. This cruise, on the Holland America Zaandam, had 7 ports of call in the Lesser Antilles, 5 along the Amazon River, and one at Devils Island – just offshore of French Guiana. While we may eventually summarize some of the key activities along the route, here we will first summarize the moths and other insects that we observed onboard the ship while it traveled along the Amazon. One of us (Mike) was providing natural history lectures on this cruise.

Slides from talks may eventually be put here, but for the moment only a kmz file for Google Earth showing select Florida nature sites is here. (This was promised during Mike’s last talk that discussed Florida nature highlights.)

To jump to sections farther down this page click on the links below:

tools for identifying what you see

Moths (This is the longest section with so many photos!)

Beetles (Coleoptera)

Flies and such (Diptera)

True Bugs (Hemiptera)

BIODIVERSITY

Biodiversity: “the variety of life on Earth, in all its forms, from genes and bacteria to entire ecosystems such as forests or coral reefs” (un.org website).

The word “biodiversity” is often in the news yet for many of us it is not always easy to appreciate the real meaning of the word. Numbers large or small do not really convey to the public the extent of biodiversity on Earth.

On our Zaandam Amazon River cruise segment (February 26-March 5, 2024) we were fortunate to witness examples of the insect biodiversity of the Amazon basin. The many insects that visited our ship every night were only a sliver of the total number of insects that inhabit such a vast area. This, no doubt, allowed many of the guests to better appreciate the meaning of biodiversity. The promenade and other suitable surfaces on different floors became a place where on a nightly basis we could all go to see the variety of insects found along the Amazon River.

Although the Amazon basin is considered one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet we did not see large numbers of birds, mammals, or reptiles. Instead we were witness to a seemingly endless variety of insects night after night during our Amazon River passage. This is not surprising, given that the total variety and number of birds, mammals, and reptiles in the world are many times lower than those of insects. About one million species of insects have been described, but it is estimated that there are many more that are yet to be identified – a more recent consensus of 5.5 million insect species (with a range 2.6–7.8 million) was estimated (Stork et al., 2015). You can read more about this fascinating topic of how many insects there are on earth at: https://rcannon992.com/2023/01/25/how-many-insects-are-there/

It is not surprising that insects were so varied given that the plant diversity in the Amazon basin is also large. Plants and insects have a history of coexistence that goes back for many millions of years. For example, many of the butterflies and moths we saw aboard need plants to eat during their caterpillar stage and later as adults many need the nectar produced by flowers. Some insects are very specialized to eat only certain plants while others are generalists and can survive on a variety of plants.

Overall, it appears that we saw many more types of moths than other insects. Nevertheless, insects belonging to many different orders and families visited our ship at night – attracted by the lights.

For us, this nightly “natural” show became one of the highlights of the cruise on the Amazon. It became our nightly insect “safari” photo shoot. Other passengers also appreciated the insect extravaganza every night and many took photos that have been shared with family and friends at home.

Due to the small size of many insects, it was necessary to use cameras with the capability for close-up photography. Many cell phones do have this capability and many guests were taking effective photos of the insects. We have specialized close-up photography equipment (“macro” lens and flash) that improved somewhat upon the iphone photography that we also did. This allowed us to appreciate the finer details of both small and larger insects. Many insects look different when we see their photos taken with a macro lens.

Most of the photos shown here were taken by Michael Douglas (naturalist/speaker for this cruise) using an Olympus EM1X or EM1 MK2 camera with (usually) a 90mm macro lens together with a ring flash. A great many iPhone photos were also taken by Rosario Douglas to obtain GPS positions and a quick identification of what we were photographing via the iNaturalist application.

Because the Olympus photos show more detail relatively few iPhone photos are included below, usually where Olympus photos were not available. We often wandered the promenade apart and sometimes one of us saw and photographed something that the other didn’t see.

All of the images have been reduced to 1920 pixels across, so the original photos have some more detail – but are too large for quick loading on our website. In fact, if you have a slow internet connection it may take time to view the images below. Also, it is best to look at these images on a large monitor. Finally, some of the moth photos have been rotated so they appear horizontal – rather than vertical as they were on the ship. This was to try to make the various species easier to compare with one another. We are not sure it does…

Tools for identifying what you see (Rosario’s views here!)

It can be daunting trying to find out what you are looking at whether it is around your backyard, on a trail or on a trip to less familiar areas. There are many apps available for your cell phone that can help you identify the plants and animals that you see. I used a few of those in the past, but it was not until I became an avid user of iNaturalist that I was really able to feel that I could find useful information for identifying nature’s many subjects. It helped me become more aware of innumerable nature subjects that can be photographed and uploaded as an observation. I can’t encourage readers enough to give it a try. It is free and there are good tutorials to help you. One feature of iNaturalist I like is that observations you submit (one photo = one observation with precise GPS location, time and date you can get by using your smart phone) can often be vetted by others and then achieve “research grade”. Those observations then go into a database that can be used by researchers. You never know what you will see and how rare or valuable that observation may be to a researcher and that adds a new level of positive reinforcement and feeling of usefulness in reporting nature subjects around you. I should mention that iNaturalist relies on the use of a smart phone and internet access before you can submit your observation. If you are in an area where there is no internet access, you can still take a photo of a subject and submit it. Any observations done when offline will be stored and your GPS position will also be stored so when you have internet you can then upload your observation and it will use your recorded GPS position.

Using my observations submitted to iNaturalist during the cruise, I have been able to get positive ID’s for many of the plants and insects we saw. iNaturalist has proven to be useful for bird identification as well. We would like to thank all the iNaturalist identifiers/curators for their valuable help identifying many of the moths featured below.

Warning: iNaturalist can become addictive

Trying to identify the insects we saw during our Amazon cruising has been fun, albeit, a very time consuming experience. Fortunately there are many resources online that can be of use when trying to learn about a particular insect. Here is an interesting site that uses a moth’s silhouette to help identify it at least to the family. This can be helpful anywhere in the world if you are trying to identify moths.

iNaturalist observations from our ship

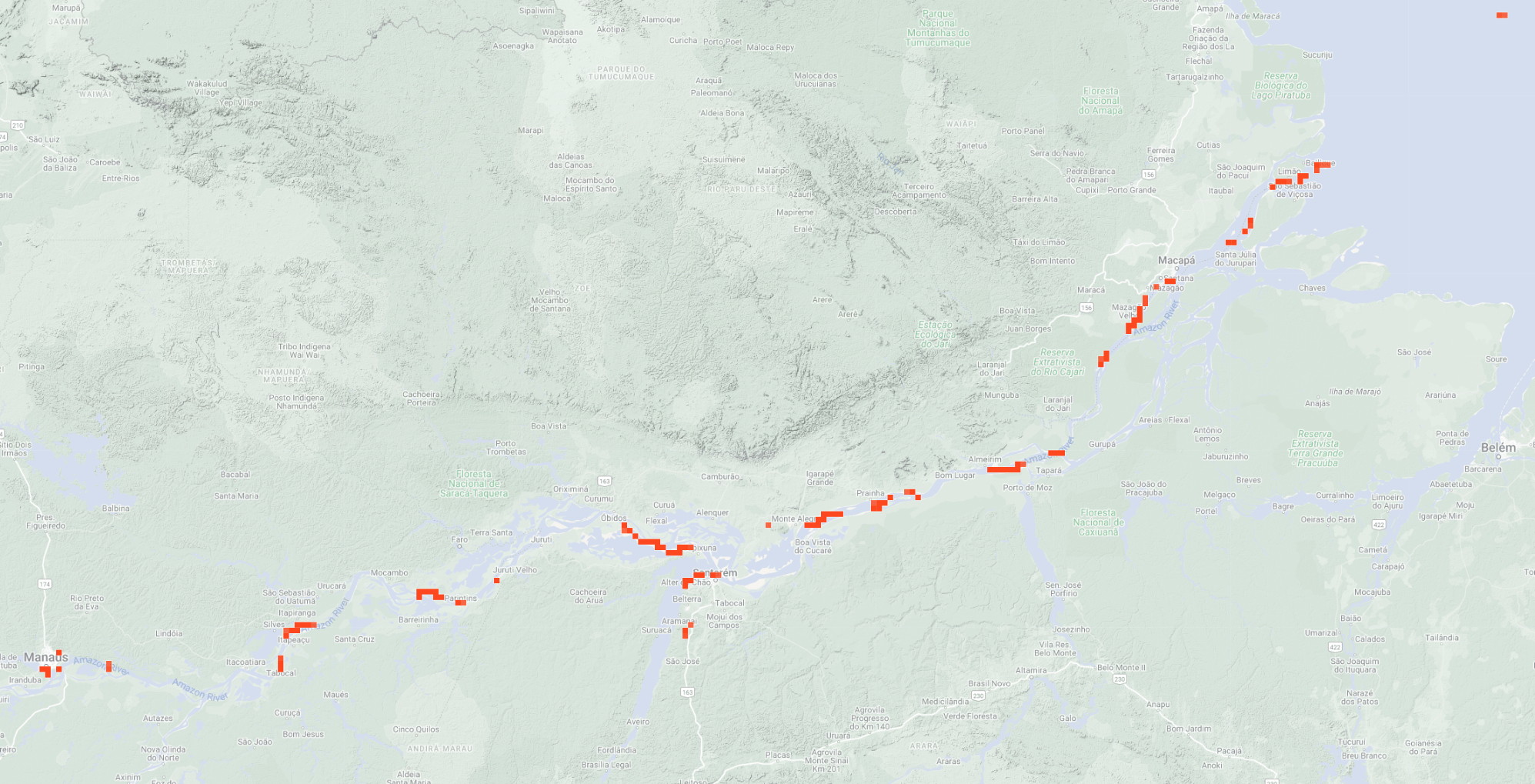

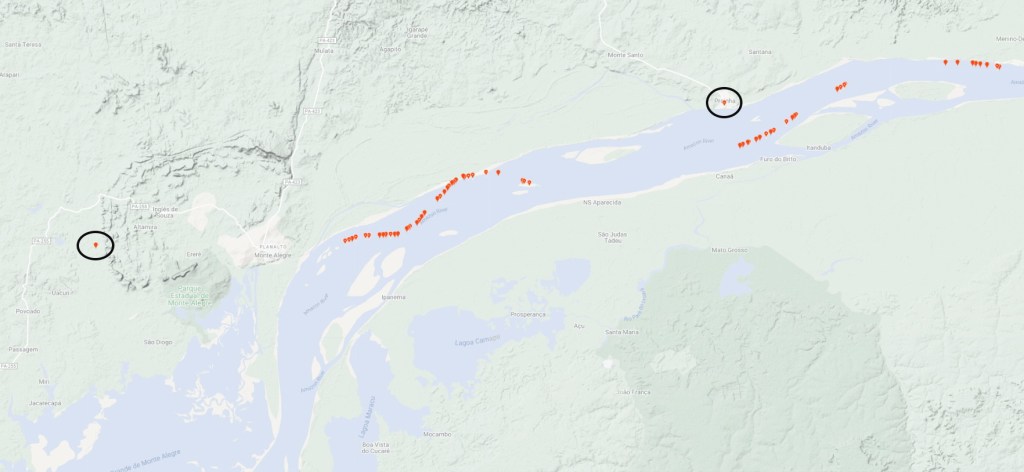

Although we obtained GPS positions from our cell phone photos, or from one of the Olympus cameras, our ship was usually moving when we made these observations. Since the ship was in the river, often some diatance from the shore, one is not really sure where to place the images of the insects. The position at the time of observation is used, but the pattern looks interesting when the observations are displayed on a map. The maps below show the positions of iNaturalist observations that we made along the Amazon.

To macro or not to macro?

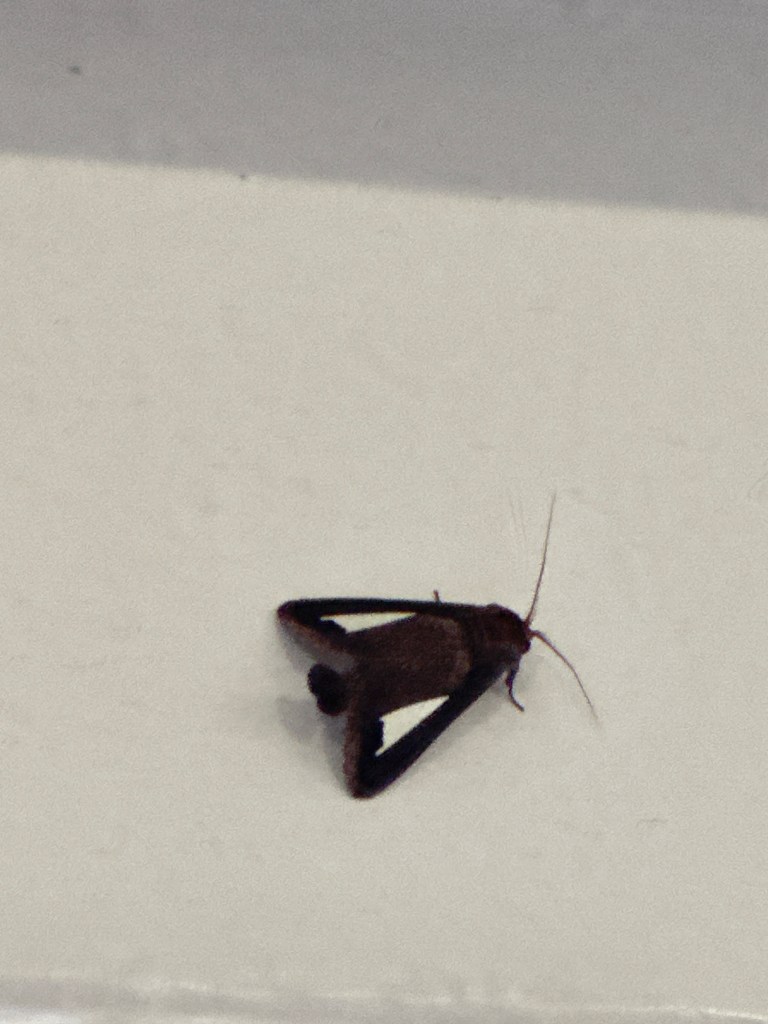

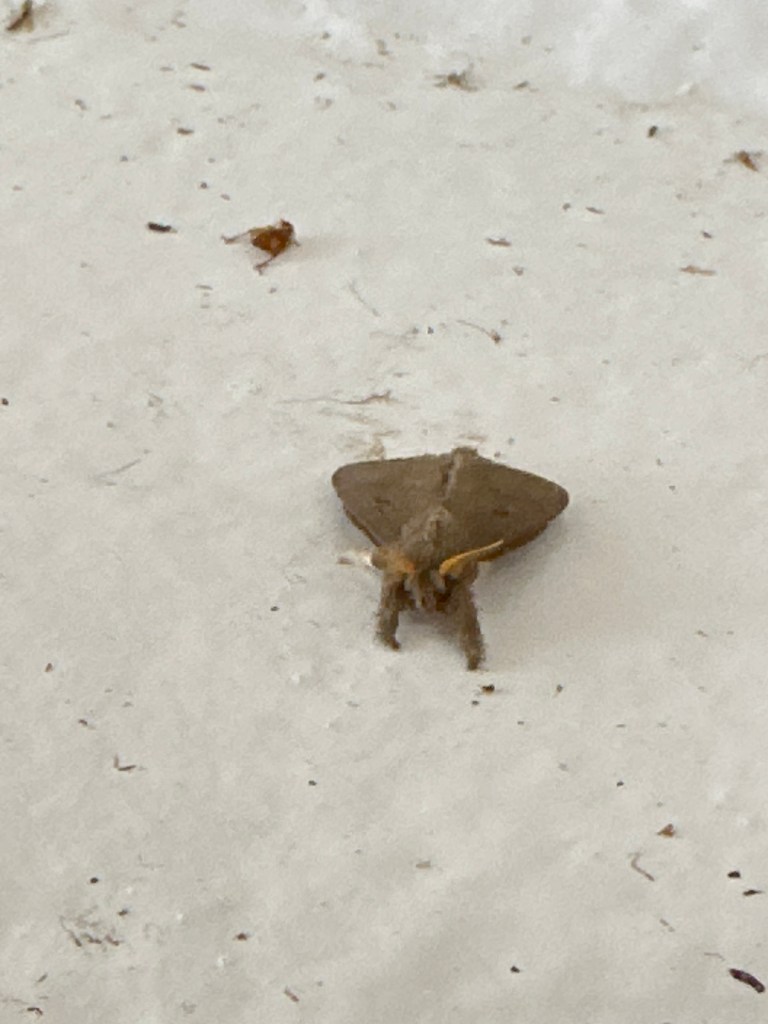

Photographing insects with an iphone is possible with some effort. Getting close and making sure there is enough light are important considerations. A macro (“close-focusing”) lens will produce a larger and sharper image of your insect or a telephoto will allow you to get “close” without physically getting as close and possibly causing the insect to flee. Below are examples of insects, photographed with an iphone 14 pro (no flash used) and the same insect photographed with an Olympus camera with a 90mm macro (close focusing) lens with a ring flash. The difference is significant. (Click on the first image in each row to see larger versions).

A new hobby

One of the most surprising and rewarding findings during this cruise was the interest that insect watching generated among some of the passengers. As lecture attendees started to see some of the pictures taken at night on the promenade as the ship cruised along the Amazon River, passengers started to come out at night to check for insects. Many started to take photos as well. More than one passenger told us they had been sending some of these pictures to family and friends back home and that in general people were amazed by the variety of insects that could be found walking along the promenade at night. The outstanding variety of insects that visited the ship every night became a perfect example to illustrate the concept of high Amazonian biodiversity.

This webpage was designed for the purpose of showing examples of the huge insect diversity we saw during our short time on the Amazon. Identifications will continue to be added to the various species shown as they become available via iNaturalist. Many of the insects we photographed have no “common name”, only scientific names (genus and species). Enjoy!

Michael and Rosario Douglas

Crypsis

Survival is a critical issue for any organism and many insects display a variety of shapes, patterns, and colors that allow them to blend in with their surroundings as much as possible. Some insects like walking sticks mimick sticks. Other insects, such as moths, that tend to spend much time on branches, bark, or leaves during the day, may resemble dead leaves or branches and even bird poop. The ability to blend in with the background to escape predation is known as crypsis.

The moths shown here were photographed on the walls of the ship along the promenade so they appear to stand out rather than to blend in, but just imagine the same moths on brown bark, or yellow or brown foliage, and you will begin to see how clever their disguises are.

Below: some cryptic moths… These moths have shapes and colors that mimic dead leaves, half-eaten nuts, or even bird droppings. CLICK on any image to start a slide show… this applies to any of the galleries below.

Mimicry

“In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species” (Wikipedia). It turns out that not only adult moths or butterflies can use mimicry to avoid predation, but many caterpillars can also do so. Biologists recognize different types of mimicry. In the case of Batesian mimicry a non-toxic organism mimics a toxic organism. Mullerian mimicry refers to two toxic organisms resembling each other. The ecological and evolutionary reasons for widespread mimicry is discussed in the Wikipedia article on mimicry.

The caterpillar stage of Hemeroplanes triptolemus, one of the many Sphinx moths we observed during our cruise along the Amazon River, is a good example of Batesian mimicry. This caterpillar is harmless and therefore a desirable prey item for birds and other predators. To avoid predation the caterpillar has evolved a tail that resembles and even moves like a snake. The imitation is so good that the caterpillar can even strike at a potential predator, presumably scaring off most predators with this behavior. You can read more about this amazing caterpillar at this site.

https://www.earthtouchnews.com/wtf/wtf/this-is-not-a-snake-its-one-of-the-best-mimics-in-nature

Order Lepidoptera: Moths and Butterflies

There are about 180,000 species of lepidopterans (winged insects that include butterflies and moths). There are 126 families in this order. Adult lepidopterans have three characteristics: Scales that cover their bodies, large triangular wings, and a proboscis to syphon nectar from flowers. The scales are modified flattened hairs that give moths and butterflies their colors and patterns. Members of this order undergo a complete metamorphosis. The larvae are called caterpillars and are very different from adults not just in appearance but also in what they eat. Caterpillars eat plants and some eat only one type of plants. Adults tend to lay their eggs near or on host larva (caterpillar) plants. A Wikipedia summary of caterpillars is here. A good example is the monarch butterfly. The adult eats nectar from a variety of flowers, but the caterpillar only eats leaves of some milkweed plants.

Many angles, one moth

An interesting aspect of moth watching is that because some try to mimic bark, branches etc, the same species of moth can look very different depending on the angle at which you take the pictures. A good example is a Canodia difformis, a moth in the family Notodontidae. The three photos were of different individuals on different days, but the same species.

Insects photographed on our 9 day cruise from the mouth of the Amazon River to Manaus and back

Below are photos of the various insects we saw during the 9 days cruising the Amazon River. We have organized the butterflies and moths by placing the photos under their respective families. Some photos are less than ideal – iPhone photos in low light tend to be not very sharp, even with flash, and some of the Olympus photos have less than ideal sharpness due to the difficulty focusing and shallow depth-of-field associated with extreme close-up photography. In retrospect, we should have spent even more time photographing the insects, but then we wouldn’t have slept at all!

Note: to see the name of each insect click on the picture. Once you do that you can advance using the arrow to see them all, one by one. We have used common names if available and the scientific name follows the common name in parenthesis. If you only see one set of names it means there are no common names.

Family Sphinguidae (Sphinx or Hawk Moths).

This is one of the 126 families of lepidopterans, in this case moths. During our trip along the Amazon we saw many species of Sphinx moths.

Sphinx moths are medium to very large in size. There are about 1450 species, mainly in the tropics. Their life span is approximately 10-30 days. Caterpillars are known as hornworms with many having preferred plants they eat during their caterpillar stage. Sphinx moths are found in a wide range of habitats.

Other moths we saw that belong to different families in the order Lepidopera are shown below. We originally placed them all together, but have now started to place them according to family. Not all our observations submitted to Inaturalist have been identified or have a confirmed ID, but we have tried to at least get to the family level of classification and if we have the ID we will have written the genus and species in the caption section. At the end of the moth section there is a category for “not yet identified”.

Family Erebidae

One of the largest moth families with many different groups of moths. Some members of this family specialize in sucking juices out of fruits and even animals (vampire moths!!). (see Wikipedia)

Family Crambidae

Crambid snout moths. (see Wikipedia)

Family Megalopygidae.

Known as flannel moths, they have stout bodies and very hairy (see Wikipedia)

Family Noctuidae

Known as owlet moths, cutworms or armyworms (see Wikipedia)

Family Aididae

Family Notodontidae

Found in most parts of the world, but concentrated in the New World tropics. (see Wikipedia)

Family Saturniidae

Medium to large size moths, although some of the largest moths (Emperor Moths, Royal Moths and Giant Silk Moths) in the world belong to this family of about 2300 species. Most species are found in tropical and subtropical regions (see Wikipedia). The caterpillar of the saturniid moth Lonomia obliqua (Giant Silkworm) is considered the most venomous caterpillar in the world. The poison is potent enough to cause human death.

Family Uraniidae

Found throughout the tropics, some species resemble butterflies and are very colorful and are called sunset moths. (see Wikipedia)

Family Nolidae

Family Geometridae

A large family. Caterpillars are called inch worms. (see Wikipedia)

Family Acrolophidae

Also known as grass tubeworm moths. (see Wikipedia)

Family Limacodidae

Also called Slug moths because the caterpillars ressemble slugs. (see Wikipedia)

Family Bombycidae

Also known as Silk worm moths. (see Wikipedia)

Family Dalceridae

Also known as jewel caterpillars, this is a small family with 80 or so species found mainly in the New World tropics. (see Wikipedia)

Family Lasiocampidae

About 2000 species of moths also known as lappet moths, snout moths, or eggars. (see Wikipedia)

Family Mimalloinidae

Also know as Sack-bearer moths. About 300 species mainly found in the tropics of the New World (see Wikipedia).

Family Sematuridae

Moths in this family are large and can be day or night flying (see Wikipedia).

Family Euteliidae

Family Cossidae

The Carpenter Miller are a large family with over 700 species found worldwide (see Wikipedia).

Family Pyralidae

A large group with over 600 species, many moths in this family are important economic pests (see Wikipedia).

Below are some of Rosario’s favorite moths

Pseudasellodes laternaria. Unusual pattern of butterflies on a moth’s wings

Eudocima collusoria. There were numerous exchanges about this moth on iNaturalist. Finally I was asked if I had collected the specimen. According to the specialist this was an uncommon moth, rare in collections and in the wild. This was the first moth I (Rosario) photographed when we entered the Amazon. We thank iNaturalist curator Bob Borth for his help identifying this and other moths.

“You’ve seen one and you’ve seen them all”

A common phrase we have all heard may seem true about moths, but often it is all about the details. On our Amazon portion of the cruise so many moths came to the lights every night that it is easy to fool the eye and say “that green one I have already seen”. The panels below are examples of green or yellow-ish moths that, at a quick glance, appear to be the same, but once you look at the details, patterns, shapes etc, you realize that they are different. The more you look at moths the better you get at seeing these differences. Besides color, with moths you will notice differences in patterns on their wings, the shapes of wings, and the types of their antenna (feathery or not). Your appreciation of “biodiversity” will increase with time.

Above: Mostly greenish moths, selected from the moths that we photographed. It is easy to think that most of these moths are similar – until they are placed side-by-side.

It is easier to see the differences among the above moths when you see them side-by-side.

Butterflies Order Lepidoptera

The other member of the order Lepidoptera are the butterflies. Moths and butterflies can look similar. Some moths look like butterflies and are active during the day like butterflies. Adults of both moths and butterflies use nectar from flowers as their main food source, but in general moths are active at night while butterflies are active during the day.

If you look closely, you will notice that butterfly antennas are club-shaped at the ends, while almost all moth antennae tend to be feathery. Butterflies tend to be more brightly colored than moths, and while both have a sense of smell, moths are considered to have a superior sense of smell.

Moths have larger scales on their wings which give them a more fluffy or furry appearance compared to butterflies, which have finer scales and thus do not appear fluffy or furry (see Wikipedia articles on moths, butterflies, and lepidoptera for more detail).

Most moths feed at night, although there are some exceptions, such as the Green-banded Urania moth which looks like a butterfly and is active during the day.

We noticed many more moths than butterflies during our cruise which makes sense given that moths are out at night and tend to be attracted to bright lights. There are many more species of moths than butterflies, though this fact may not be apparent to most people who don’t spend most of their time outside at night.

Below are some of the butterflies we photographed on the ship as well as some photographed in the daytime during some of our shore excursions.

Family Pieridae

Found mainly in tropical Asia and Africa . (see Wikipedia)

Family Lycanidae

Also known as brush-footed butterflies. Second largest family of butterflies. (see Wikipedia)

Family Nymphalidae

Also known as Brush-footed butterflies. The largest family of butterfly with over 6000 species. Species in the genus Caligo are known as Owl butterflies because of the large eyespots that resemble owl’ eyes on their wings. (see Wikipdia)

Family Hesperidae

Also known as Skippers. Named for their quick darting habits. (see Wikipedia)

Caterpillars

Prior to becoming adults both moths and butterflies undergo a series of stages, a process called metamorphosis. This link provides useful information about metamorphosis. . Caterpillars or larvae are one of the pre-adult stages of moths and butterflies and they can look very different from what the adult will look like once the metamorphosis process is completed. We did not see any caterpillars on the ship, not surprisingly since they eat plants, flowers or roots at this stage. During our excursion to MUSA Museu da Amazonia in Manaus we noticed a couple of very interesting caterpillars who in order to avoid predation were trying to look like bird poop and perhaps a branch with hanging small branches.

The images below show our photos of the caterpillars and their respective adult stages. The illustrations of the adult moth and butterflies are in the public domain (Wikipedia)

Order Coleoptera (Beetles)

Beetles are placed in the largest of all orders, the order Coleoptera. There are about 400,000 described species of beetles which makes them about 40% of all known insects. New species are still being discovered and named.

In order to provide an example of the great diversity of beetles we have include below an image from the collection of beetles at the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Germany (Wikipedia Creative Commons).

Curiously, during our time on the Amazon River we saw many more moths than beetles coming to the lights. We are not sure how strongly beetles attracted to lights, as is the case with moths. We also hypothesize that beetles do not fly as far as moths. Since the ship was not always close to the shore, this could be an explanation for the fewer variety of beetles observed. None-the-less, we still saw many beetles, featuring a variety of patterns, sizes, shapes, and types and length of antenna (see Wikipedia for more about beetles).

Below are some of the beetles that visited our ship while on the Amazon. If available, you can see the identification by clicking on each photo. As more ID’s come become available from iNaturalist, we will add them to this gallery.

Order Diptera

A very large order of insects containing over a million described species including horse flies, crane flies, hoverflies, mosquitoes and others (see Wikipedia).

Above: Some flies… members of the insect order Diptera. Note the compound eyes of the flies and the feathery antennas of the mosquito-like insect on the left. Compound eyes are made up of thousands of independent photoreceptors which allows a faster reaction to movement.

Order Hemiptera (true bugs)

Hemipterans are a large group of insects with about 80,000 known species including insects such as: cicadas, assassin bugs, bed bugs, aphids, plant hoppers and shield bugs. They have sharply pointed tube-like mouthparts (proboscis) which are used for piercing or sucking. Most hemipterans feed on plants, but some are known to feed on blood (see Wikipedia for more information).

“Bugs” versus insects

All insects (including those in the order Hemiptera) belong to the class Insecta and are thus considered to be insects. It is very common to hear the word “bug” being misapplied to any insect people see. However, in proper entomological terms (entomology being the branch of zoology that deals with the study of all insects), this term is reserved only for insects in the order Hemiptera – the so-called “true bugs”. See the post titled What is a bug? from the blog Biological Linguistics for a short explanation of the usage of the word “bug”.

Order Neuroptera (Net-winged insects)

The name neuroptera refers to the complex vein patterns on the wings. This insect order of about 6000 species includes the lacewings, mantis flies as well as antlions (see Wikipedia for more information).

Order Odonata (Dragonflies and Damselflies)

Members of this order are predatory (almost entirely insectivorous) both as adults and in their aquatic larval stage. Dragonflies (suborder Epiprocta) are bulkier with large compound eyes that are close together and they tend to keep their wings spread up or out when at rest. Damselflies (suborder Zygptera) have slender bodies, their eyes are placed apart, and they fold their wings along the body when at rest (see Wikipedia).