The deserts of North America fall into different classifications based on mean annual temperature, seasonality of precipitation and the likes. Common to all deserts is their aridity – the potential evaporation must exceed precipitation. Potential evaporation (or evapotranspiration if you want to include water loss from plants) is commonly used because there might be no water to evaporate most of the time.

While there are many subdivisions that can be made for the North America arid zones, a commonly used broad classification breaks the arid lands into a Great Basin Desert, a Sonoran Desert and a Chihuahuan Desert. The Mojave Desert is usually also considered a separate desert, and sits as a transition between the lower-elevation Sonoran Desert to the south and higher elevation drylands of the Great Basin and Navajo Plateau to the north and northeast.

As we may have stated elsewhere on our website, maps are critical to travel planning. The US National Park Service produces very valuable maps for all of the US National Parks. It is tedious to hunt through each park’s webpage to find maps to download. Fortunately, one individual has produced a website that provides access to virtually all of the maps produced by the NPS. The maps are organized by park and by state. The site really is invaluable to US nature travel planning.

Perhaps the best online discussion of the Sonoran desert can be found on the website of the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum (ASDM), outside of Tucson, Arizona. This material is part of a book written on the Sonoran Desert by staff at the ASDM. However, we would recommend purchasing the second edition of this book for the more serious naturalist. We won’t repeat here the extensive discussion of the online material. The Sonoran Desert has received perhaps the greatest attention of the various American deserts because of the human populations living in the region. Also, the Sonoran Desert has characteristics that are “stereotypical” of what most people consider a desert to have.

The Sonoran Desert is named after the Mexican state of Sonora, but the Sonoran Desert extends from near Palm Springs, California to southern Sonora (and even a coastal strip of Sinaloa) and includes most of the Baja California peninsula. However, it is certainly not uniform across this huge region, and variations in elevation, rainfall and temperature determine the characteristics of the plants and animals found in different parts of the Sonoran Desert.

Like in most deserts of the world, sand dunes are only a small part of the Sonoran Desert, but these areas have interesting flora and fauna adapted to them.

The Sonoran Desert flora is perhaps best known for its cacti, which include many species of cholla (Cylindropuntia) and hedgehog (Echinocereus) cacti. There are relatively few species of large cacti, but they have large ranges. These include the Saguaro, Organ Pipe, Senita, and in Baja California and Sonora tho types of Cardon. While this may seem like a fair variety of large cacti, there are small valleys in southern Mexico where you can find twice this many species of large cacti!

There are quite a few succulent plants that are not members of the Cactus family found in the Sonoran desert. These include Yucca and Agave – these succulents are often found in higher elevation and moister parts of the desert.

Despite the prominence of succulent plants in the Sonoran Desert, the most common plant species is almost certainly the Creosote Bush (Larrea diviricata). The crushed leaves smell like creosote, and the desert with Larrea has a distinctive smell like creosote after a rain shower. The Creosote Bush is also found in the Chihuahuan Desert, but not the winter cold Great Basin Desert. More than any other plant, the presence of Creosote Bush tells you that you are in a North American Desert.

Because the Sonoran Desert has only rare periods of freezing temperature and has a direct connection to the tropics via the coastal plain and foothills along the eastern side of the Gulf of California, many animals can migrate into the Sonoran Desert from the south. During the summer months many species of hummingbirds move northward into the southeastern part of Arizona (usually just above the Sonoran Desert) to take advantage of vegetation flowering during the summer rainy period. Even Jaguars have been seen in southeast Arizona – normally residents farther south in Mexico. And many species of reptiles and amphibians are only found in the US in southern Arizona. These of course don’t migrate seasonally, but there are no oceanic barriers to the northward migration of tropical species as there might be for example in the eastern US.

Where to see the Sonoran Desert in the US

For most US naturalists the most convenient places to explore the Sonoran Desert are in southern Arizona and southern California. Driving through this region on highways it should be possible to stop in many locations to explore. However, freeways and some other major highways are not the best for exploration because they are usually fenced to prevent (wild) animals from entering the roadway and you cannot leave the highway right-of-way, even in desert areas. The best locations for exploration are national or state parks or Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land that usually have networks of dirt roads for access. In these areas you can stop your vehicle almost anywhere (safely off the road of course) and walk through the terrain without preoccupation with crossing private property or being blocked by fences.

The Sonoran Desert is not the same everywhere, and is broken down into subdivisions by geographers. In the east, near Tucson, it has both winter and summer rain and many of the species, of both plants and animals, differ from those found in the western-most, rain-shadow Sonoran Desert in southern California where rainfall is mostly during the winter and is about half the amount found near Tucson. Fortunately, good parks exist across much of the Sonoran Desert to explore the desert’s variations. In southern California, there is Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, one of the largest state parks in the US. Information for the Anza-Borrego region useful for the naturalist can be found here. The park extends from near 6000 ft to just above sea-level, and ranges from Pinyon-Juniper woodland at higher elevations to sand dunes, badlands, and desert washes in the lower parts of the park.

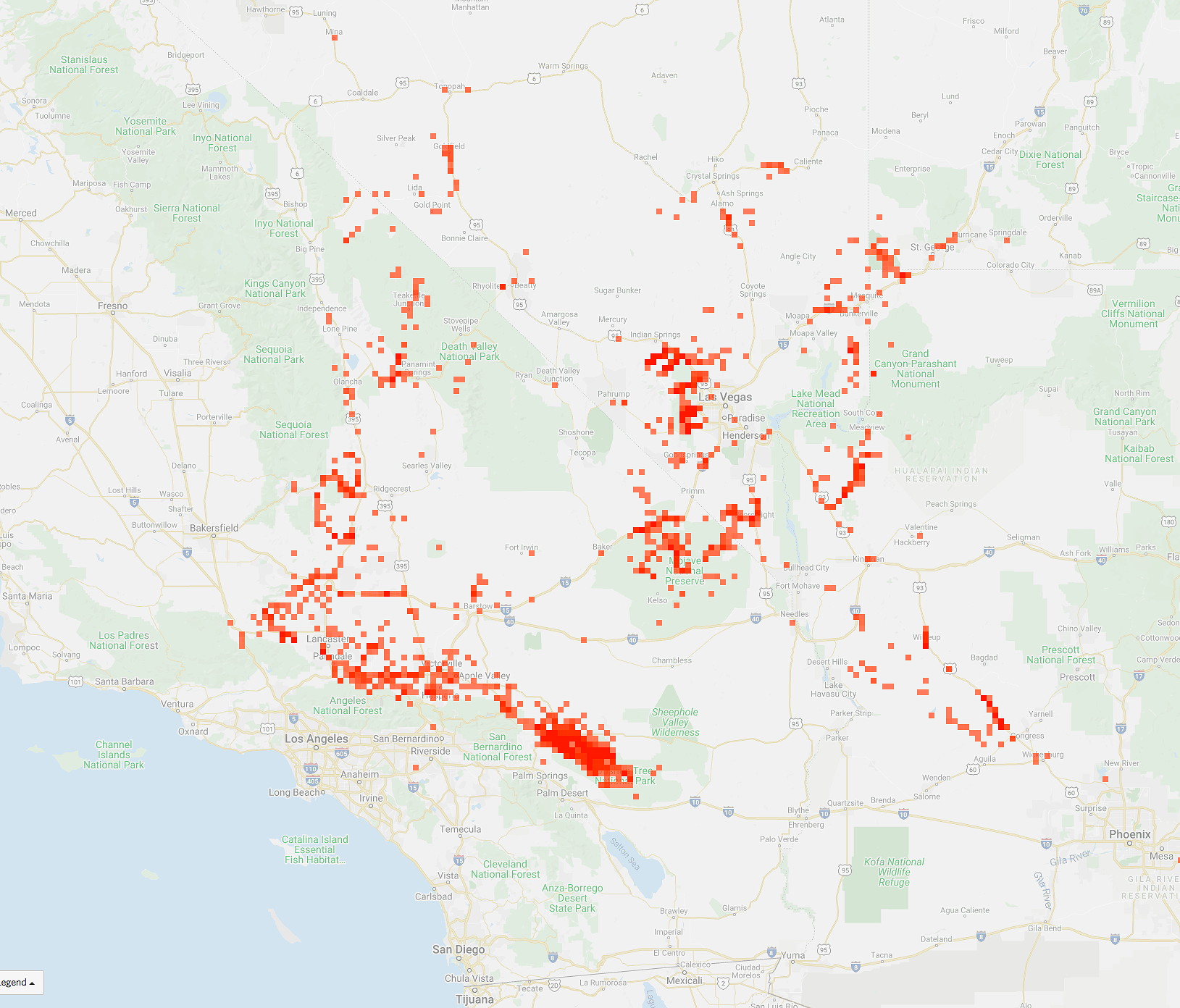

We describe some areas of the Mojave Desert (see Fig. 1) here since a visitor will likely travel through the Mojave on their way to Los Vegas, Phoenix, or Los Angeles. Many consider the Mojave to be a transition desert between the warmer Sonoran and the colder Great Basin Desert (not shown on Fig. 1‘s map). The Mojave Desert is sometimes considered to be approximately defined by the distribution (Fig. 2) of the large Joshua Tree (Yucca brevifolia).

A collage of Cylindropuntia bigelovii photos is shown below. It is one of our favorite/feared cacti and will forever be treated with respect by desert explorers after a first painful encounter.

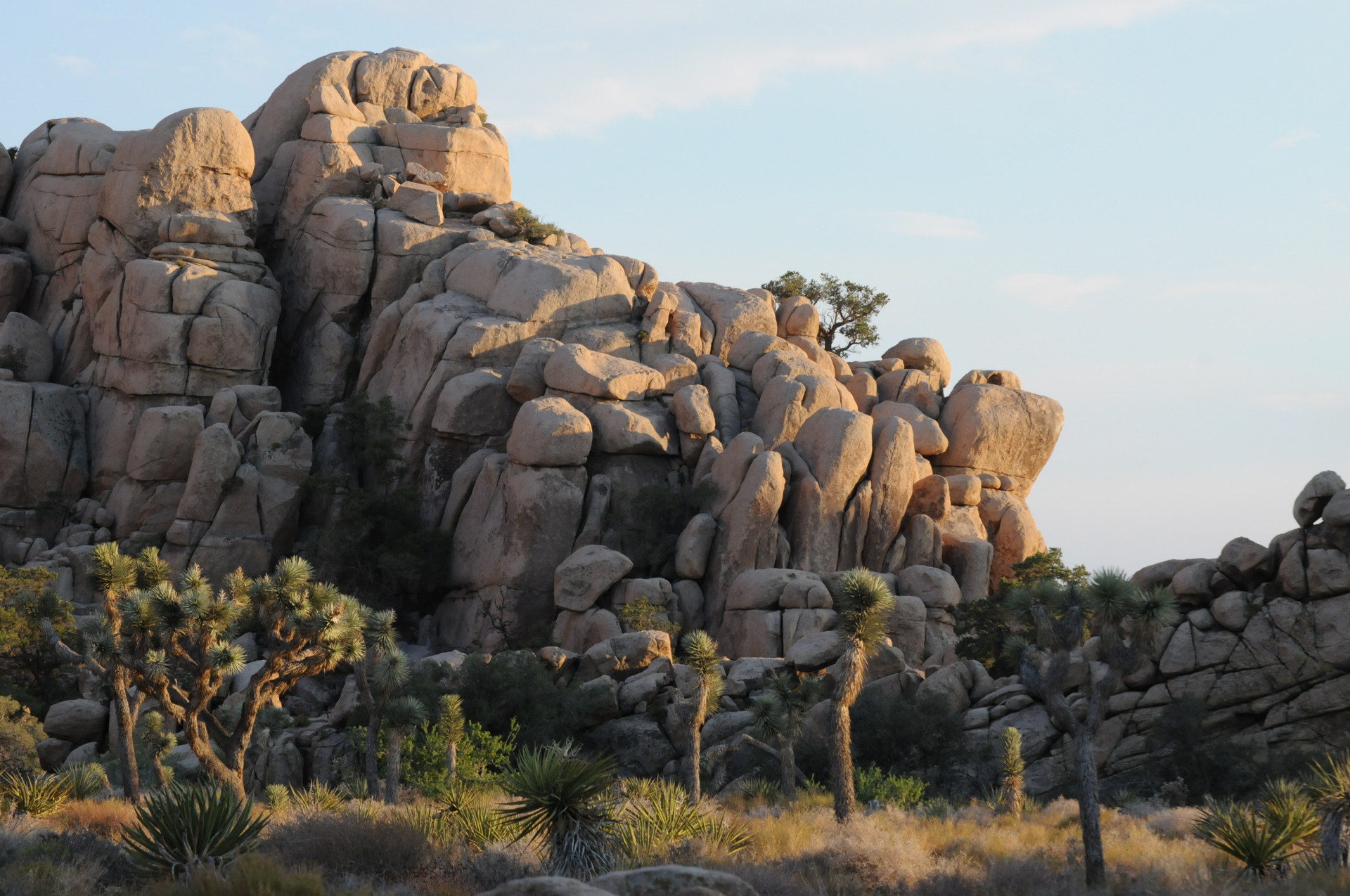

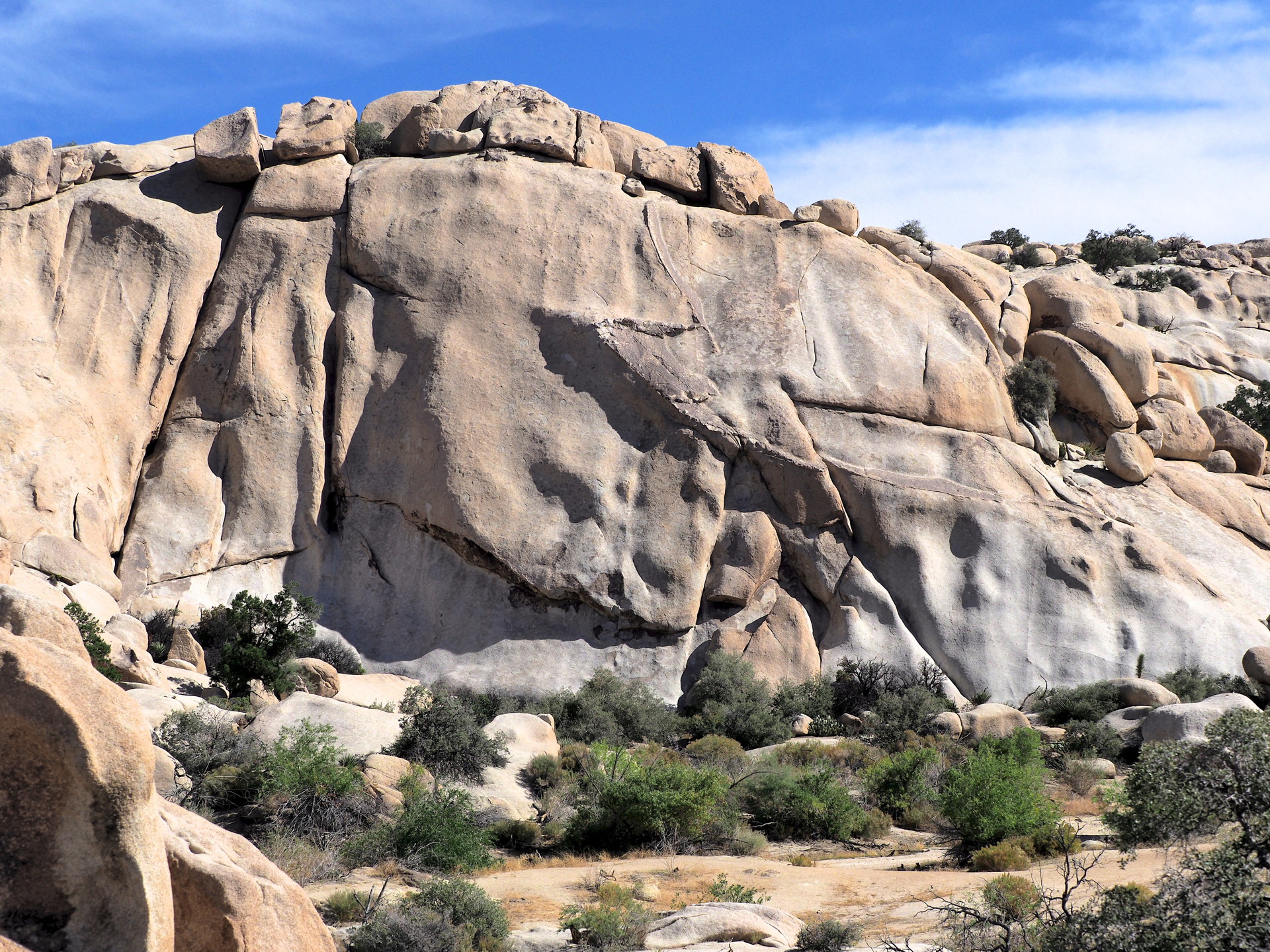

East of the Los Angeles, Joshua Tree National Park includes both higher elevation desert terrain with Joshua Trees and low desert landscapes. It is a transition zone between the higher elevation Mojave and lower elevation Colorado Deserts.

Most people visiting Joshua Tree NP will approach it from the direction of Los Angeles – through the Banning Pass – a low gap between two high mountains. This pass is usually windy – especially in summer and is the site of the largest, or at least the most concentrated array of wind turbines almost anywhere.

The Mojave Desert lies to the north of the Sonoran Desert and is generally considered separate from the Sonoran Desert. There is no clear boundary between the two, but freezing conditions are more frequent in the Mojave Desert and summer rain is infrequent.

Joshua Tree National Park lies in the transition between the two deserts; one can drive northward through the park and ascend from the Sonoran Desert into the higher elevation Joshua Tree woodland. The park gets relatively heavy visitation due to its proximity to Los Angeles, and is least crowded on weekdays in the Summer. Of course it can be quite hot in summer – even at 4000 ft elevation – so fall or winter weekdays are more comfortable. The park has many camping sites, but these are relatively primitive by US camping standards – all lack electricity. However, most sites are located in very scenic landscapes.

Northeast of Joshua Tree National Park is the Mojave National Preserve. This area lies between two major freeways yet is lightly visited as it lacks major campgrounds and visitor centers. However, several good paved and many dirt roads cross the preserve and the excellent Joshua Tree forests are found in parts of the preserve. The large Kelso sand dunes and some volcanic features (cinder cones and lava flows) are also present.

The iconic Sonoran Desert that is best known to foreigners and even to most people from the eastern US is that found around Tucson and Phoenix, Arizona. The dominant plant, or at least the most obvious one to out-of-staters is the Saguaro (pronounced “Sa-warh-row”), a tall cactus (Carnegiea gigantea). Although a few plants are found in California near the Colorado River, nearly all Saguaro are found in Arizona and in the bordering Mexican state of Sonora. The densest “forests” of Saguaro are found around Tucson, in the Saguaro National Park. This park has two parts – one west and the other east of Tucson. This is one of the best areas to see these cacti and the typical Sonoran Desert in which they occur.

A large County Park with many hiking trails also borders the National Park west of Tucson and within this park there is the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. This “Museum” is imbedded within natural terrain and is an essential stop for the naturalist traveler. You can easily spend half a day – the Museum is mostly outdoors and has many animal and plant displays embedded within the natural Sonoran Desert landscape.

This landscape in Saguaro National Park is dominated by the Saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea)

Another Saguaro landscape in late afternoon. By the way, it is pronounced “saw-wuar-o“, not “sag-u-are-o”.

There are some picnic facilities and many hiking trails in Saguaro National Park. Overnight camping is just outside the western part of the park in the county-managed Tucson Mountain Park.

The other reserve that is part of the US National Park Service is Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument about 3 hours west of Tucson. It lies along the US-Mexico border and is somewhat drier than the parks around Tucson. A large campground is available in the Monument, but otherwise US motels are only available 40 miles north in Ajo. This park is much less visited than those around Tucson, especially the dirt roads that traverse the back country of the park. These are highly recommended (one is suitable for regular sedan cars while the other benefits from high clearance).

In addition to Saguaro cacti, the Monument has the best displays (in the US) of the Organ Pipe Cactus (Stenocereus thurberi). Another large cactus, the Senita (Lophocereus schottii), is only found in the US here. Both the Organ Pipe and Senita are common in Mexico – extending to the tip of Baja California.

In addition to the major National Parks, there are a number of state parks in Arizona that permit access to the desert. Of course, many of the dirt roads in desert areas cross lands managed by the BLM and primitive camping is available on this land.

Sonoran Desert climate

Travelers to the US Sonoran Desert need to be familiar with the climate of the region because the Sonoran Desert is the hottest part of the US in summer. As such, some naturalist travel itineraries can be uncomfortable or even dangerous if a vehicle failure happens. Typical monthly means temperatures for a few select cities are typical of the lower Sonoran Desert and are shown in the figure below. By Googling you can find monthly mean values for almost any sizable location by putting the name of the location and “monthly mean climate”. A good one that has more climate stations than any other is available from the Western Regional Climate Center’s page, a specific map to click on is here. Select the state then select the station you want. You will get monthly mean values for max and min temperature, precipitation etc for the period of record of the station.

Of course, there are the weekend visits by locals to natural history destinations during the peak period from October to May. Much of the southern California desert is within a few hours drive of Los Angeles or San Diego and there is a large influx to weekend campers into the deserts starting on Friday and with huge returns on Sunday afternoon. Out-of-state and foreign tourists should try to visit the coastal regions of Southern Caifornia on the weekends and the mountain and desert locations during the week from Monday to Thursday if at all possible. The same could be argued for the Arizona low deserts in winter.

Suggestions for visiting

Visitors to North America should be aware of the “snowbird” phenomena. A great many retired Americans travel south in motorhomes or other large recreational vehicles for the winter months – especially if they live in the northeastern US where the cold and cloudy conditions are unpleasant. These people noticeably increase congestion in cities like Tucson and Phoenix and especially in smaller towns like Yuma where there are huge recreational vehicle (RV) parks of various kinds. While most of these visitors don’t seriously impact the more remote natural areas, some do. Campsites near Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and around Tucson are often near capacity from December to April with RV’s. These RV’s also either tow off-road capable vehicles or are towed by them, so that even dirt roads can be more congested during the snowbird season.

The short advice is that winter and spring are best for visiting the low desert for seeing annual wildflowers and landscapes and for desert hiking. Cacti can flower from Feb to June, depending on altitude and species. For nocturnal snakes summer and early fall is best, and for frogs and toads after summer rainstorms (sporadic) is best. It is simply too hot to enjoyably camp and hike in the low desert during June through early September, though if you shift to a nocturnal mode hotel accommodations are definitely in a “low-season” mode. Also, a great benefit of summer camping is that you will have the parks all to yourself! Except of course, parks with lakes, where fishermen will be found all year.

There are a few caveats to the timing of your travel to see the Sonoran Desert. It is almost unavoidable to visit the fringes of the Sonoran Desert – those areas with greater rainfall and different flora and fauna. These areas are typically the mountain ranges bordering the lowland desert. If your focus is on hummingbirds and reptiles and amphibians of the southwest, late summer may be the best time to visit the region. SE Arizona is a well-known destination for birders in summer when hummingbirds from NW Mexico migrate northward with the availability of insects and flowers associated with the summer rainy season. This is only true in SE Arizona – western Arizona and Southern California do not see a pronounced summer rainy season. Of course, conditions during summer are noticeably warmer and the best camping locations are at elevations above the Sonoran Desert – ideally in mountain locations.

Some basic biogeographical aspects of the Sonoran Desert

While there are many website describing the Sonoran Desert, we note here a few aspects that you won’t casually come across.

Cholla diversity greatest of any region. Cholla cactus (the genus Cylindropuntia) are usually not the favorites of most people, since their pieces tend to sick to boots, plant and most anything that touches them. That is how they reproduce (vegetatively). But they are dominant species in parts of the southwestern deserts and their greatest diversity is in the Sonoran Desert. So keep a look out for the many species that you will see. A few of the commoner cholla cacti are shown below. Some are widespread, while others are rare and quite localized.

Be aware of the many microhabitats of this (and other deserts). Here we describe a few characteristics of deserts in general. An nice summary of desert landforms can be found here. A good description by the US Geological Survey of the Mojave National Preserve landforms and surface geological features is here.

Like most arid regions of the world, the entire southwestern US has usually-dry rivers called “washes“. These are typically dry 99% of the time – except after rains. People die every year in flash floods when these washes quickly fill with water after heavy summer storms and they try to drive through the water. There are some interesting videos online about flash floods – in fact there are even flash-flood chasers, much like tornado chasers, who try to anticipate flash floods and then video the arrival of the water. A couple of online videos are here and here. Flash floods don’t only occur in deserts but they are best known from these regions.

Returning to washes – these can be narrow enough that you can jump across, or a mile or more wide with many smaller anastomosing channels. They are interesting habitats for species of plants or animals that are found only in, or near them. In the California deserts the Smoke Tree (Dalea spinosa) is a clear indicator of large washes as the tree survives on subterranean water associated with washes. Sidewinder rattlesnakes, though not restricted to washes, find the soft wash sand ideal for burrowing during the day. So do some other burrowing snakes. Javalina hide during the day often in the denser vegetation of some washes.

Alluvial fans are outflows from canyons where large bounders and other stones are deposited. These fans are found at the base of most desert mountains and have distinct flora. Alluvial fans can merge together from multiple canyons and form bajadas – gently sloping terrain that are almost the same in appearance as alluvial fans, only much larger. Farther away from the bajadas are silty flats often with dry (salt) lakes present. These silty/saline soils have the least plant and animal diversity, though they can have some unusual salt-tolerant species.

Sand dunes are not widespread in North American deserts, but they do occur – almost always in association with dry lakes and their finer sediments. The largest dune field in the Southwest US is between El Centro, California and Yuma, Arizona. The dry lake providing the fine sediments was the large salt flat now covered by the Salton Sea (man-made by accident in 1905). Thus dunes have lost their source of sediments, but it will be a long time before they disappear.

In general, small dune fields with vegetation covering parts of the dunes have the most interesting wildlife. These should be explored near sunrise or sunset; specialized Fringe-toed Sand Lizards and some snakes like Sidewinders and burrowers like Shovel-nosed Snakes may frequent these dune fields. Careful examination of Google Earth imagery may be required to identify suitable and accessible dune fields.

Desert Pavement refers to a desert surface covered by closely-fitting stones. This is not accident; the wind and water have removed finer particles in the surface layer and the stones are too large to be removed by wind, and by water on flat terrain (desert pavement is not found on steep slopes because flowing water could move the stones…). Since the fine material is removed, leaving only stones, the surface looks like a coarse pavement. This pavement can cover huge areas, but unfortunately vehicles can mar the surface for many decades. The surface of the stones is dark, with a covering called desert varnish – a product of chemical reactions on the surface of the stone exposed to the air (tip over a rock – the bottom doesn’t have desert varnish).

Rocky hillsides are the habitat for many succulent plants, especially cacti that require good drainage. Usually the exposure is important in determining the vegetation density – southwest facing slopes are hottest and northeast facing slopes are cooler and moister on average (as anywhere in the northern hemisphere).

Large oases are not common in the Sonoran Desert and are different from those found in Africa or the Middle East. Excluding the artificial date palm plantations in California and Arizona, the main natural oases are those in canyons of mountain ranges bordering the Sonoran Desert. The California Fan Palm (Washingtonia filifera) is found in these low-altitude canyons.

Finally, there are a number of streams that extend from mountains into the upper reaches of the desert. These riparian areas are corridors for fauna requiring steady moisture and the trees typically are dominated by cottonwoods (e.g. Populus fremontii).

Some representative wildlife of the Sonoran Desert

It is impossible to cover most of the major vertebrates of this desert (let alone invertebrates), but there are a few that are common and representative of the southwestern US deserts. Some extend beyond the boundaries of the Sonoran Desert.

Birds are perhaps the most commonly seen or heard vertebrates of the low desert. Some of the common ones are shown below – many other common ones we don’t have good photos of, but the traveler will of course have a bird book of North America if traveling to the region.

Our discussion above has only covered the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and California. The Sonoran Desert also extends far into Baja California and into the Mexican state of Sonora. For a discussion of Baja California see our webpage here. We have spent extensive time in Sonora but have not written up the material and not visited in recent years (since 2004).